For longtime subscribers to Real Koreans, hello! It's Emily—it's been a while. As you may know, I started this blog to write about things I was passionate about, which was mainly feminism, youth rights, and LGBT community updates in South Korea. I've stopped writing for a while, because I was unsure what I had to say about Korea, having moved away in 2014.

In my 11th year abroad, I finally know what I have to say, which is the same as back then: writing about things I care about, which will include Korea, but also many other topics, like analysing my favourite arts & culture scenes (like today), how to deal with anti-Asian racism in Europe, and my experiences working in global nonprofits.

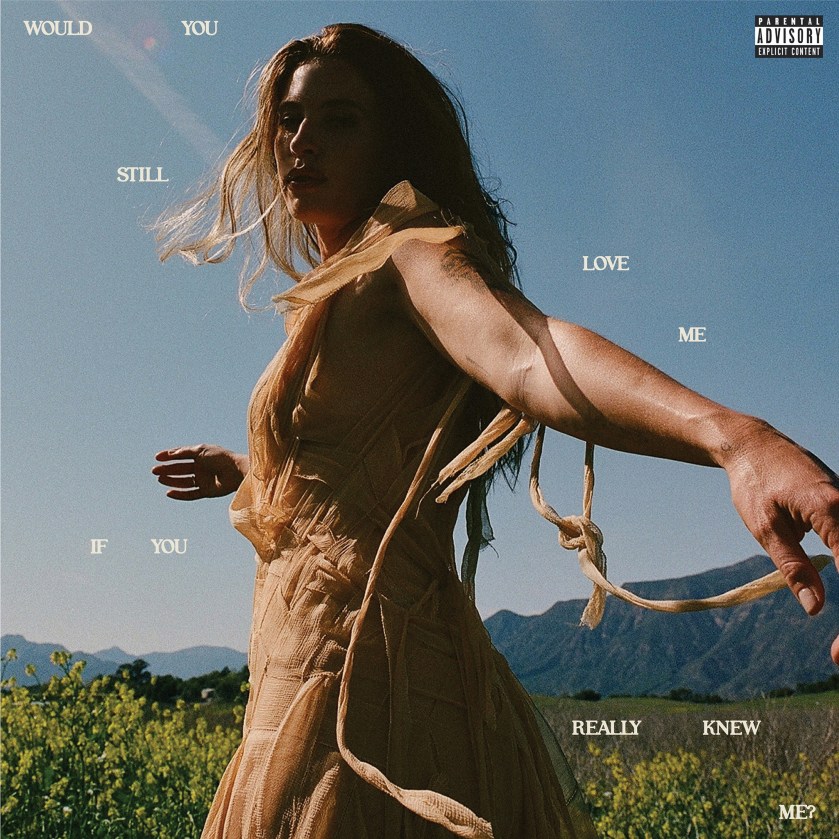

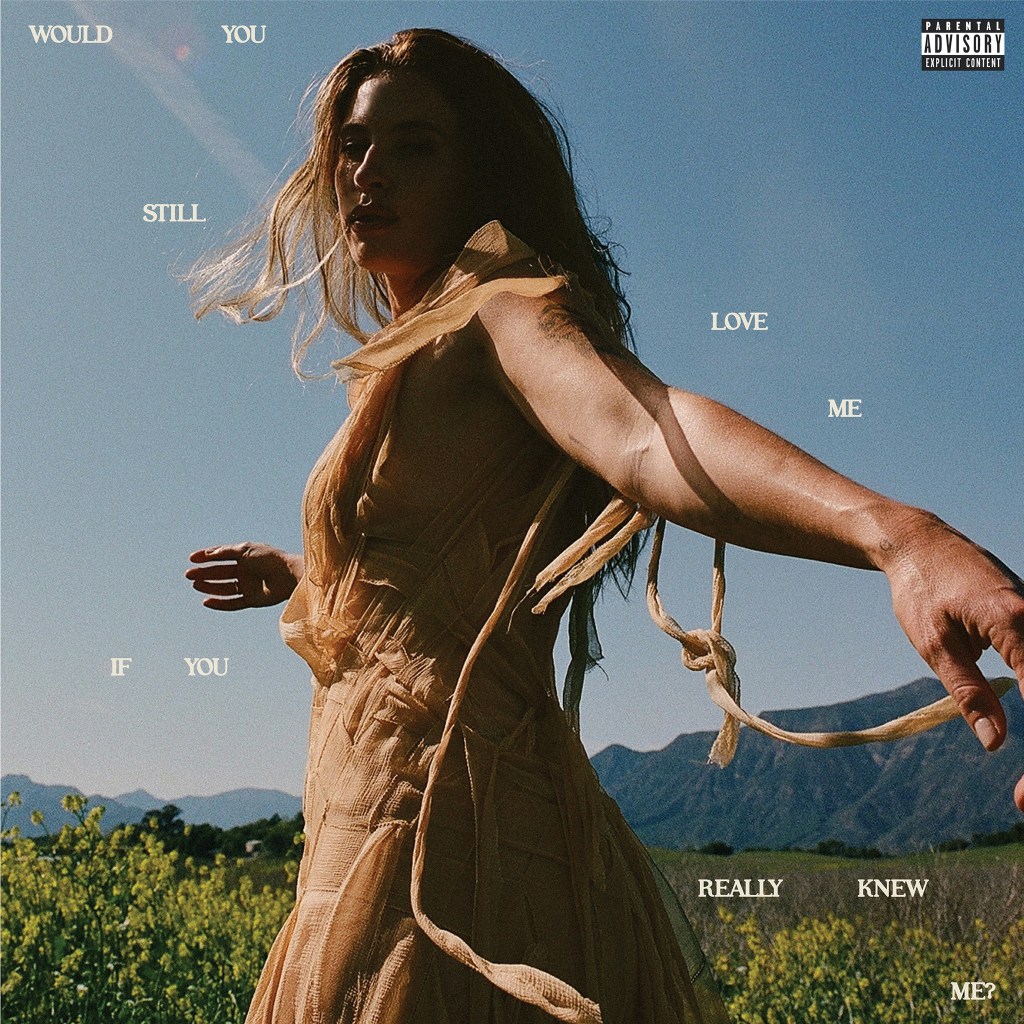

The sapphic Internet has been up in flames the past three days over a new release from FLETCHER, in which the lesbian icon confesses to being in love with a man. While she last alluded to seeing someone in an interview June last year, there was no build-up to this major pivot in the singer-songwriter’s decade-long dedication to wlw (women loving women) music.

While debates are ongoing, and PR professional Lauren Beeching has already excellently summarized how Fletcher’s campaign has failed spectacularly (tl;dr: don’t make major announcements which may alienate your fanbase without a dedicated care campaign beforehand), I have two questions and an observation that haven’t yet been shared by others.

What I noticed as a fan (and fellow queer woman)

On June 5, FLETCHER released Boy, a single from her upcoming album. I was excited to see this pop up on my Spotify, since it’s almost been a year since I saw her live at Paradiso Amsterdam on April 9. I listened to the song twice, and it resonated deeply with me, as a queer woman who has had to come out multiple times over the past decade.

I’ve been sitting on a secret […]

Laying my cards on the table

I’ll admit I don’t know how to label it

[…] And only time will tell

If I will or won’t do this again

Maybe I’ve changed or maybe it’s just him

FLETCHER addresses the uncertainty of her relationship and development in her sexuality. She has mentioned having dated men in her music (Girl of My Dreams, 2021) and consistently corrected people calling her ‘lesbian’ (preferring the term ‘queer’), most recently in a June 2024 interview with The Cut. But what most fans love her for is her music of the past decade, exclusively dedicated to relationships, breakups, and aftermaths of loving women, a rarity in mainstream pop.

Most fans seem to agree that it is the delivery and timing of the release and abrupt campaign, not the announcement per se, that is the problem: We stand by your identity, but why are you choosing to release this, a seemingly heterosexuality-celebrating, lesbian-past-denying song, during Pride Month, when American queer rights are under attack more than ever? Your song is going to be weaponised against us lesbian women to say: see, you just have to find the right man, like this young lady right here.

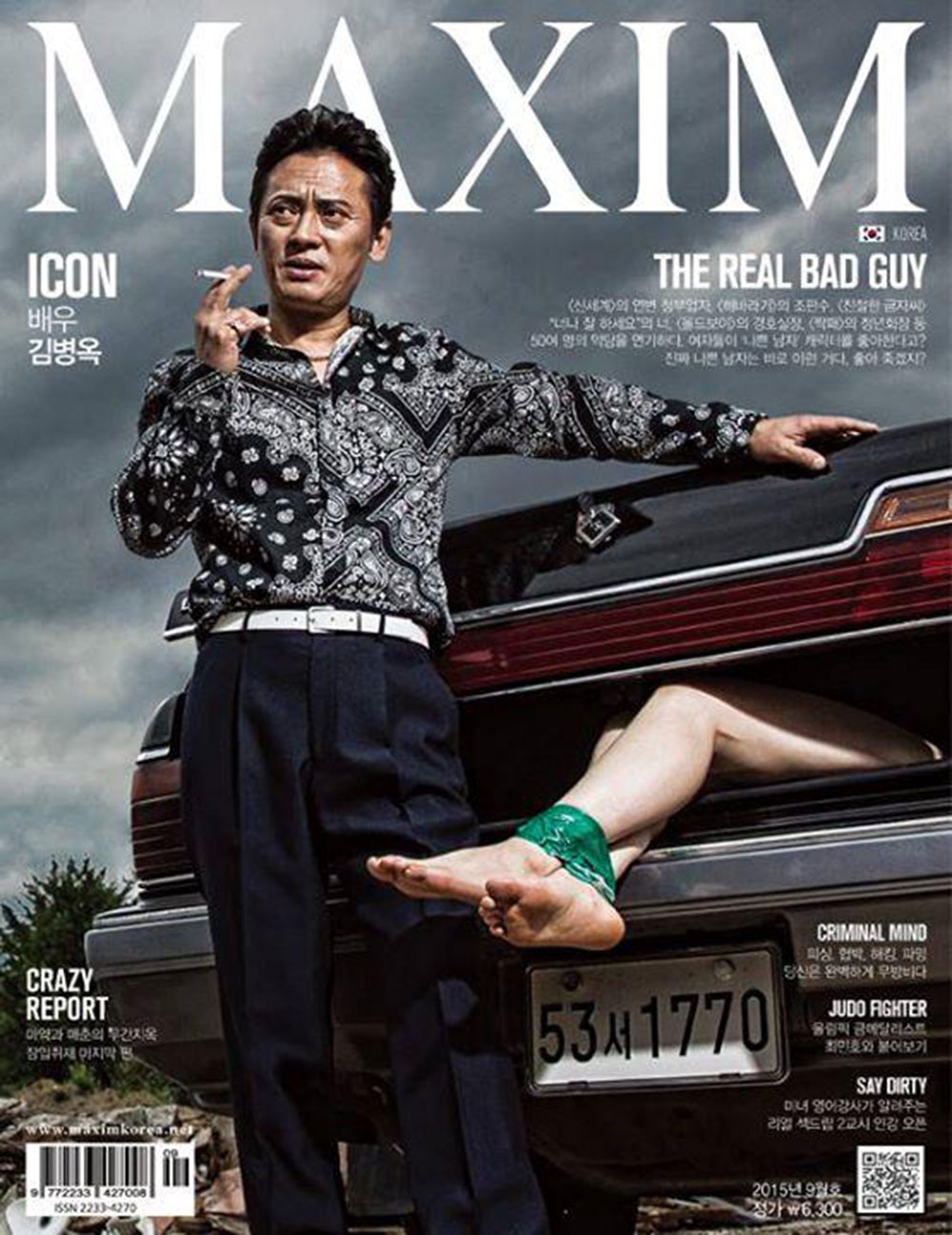

Not to mention the disappointment and hurt in yet another messaging which seems to declare: “I was a mess. I was chaotic and sleeping around, but I found a man. Now I’m in my mentally stable, happy era”. This made me think of Miley Cyrus’s song, Malibu, which in itself I find to be beautiful (and a a karaoke favourite), but both songs seem to press on the same imagery of a woman being rescued from her inner torment (and late night sins) by a man, symbolised by them swapping mesh tops and hot pants against a busy nightlife scene with beige clothes on a field of grass:

What I noticed, as a communications professional

There are no A-list (queer) celebrities to be seen on FLETCHER’s social media accounts, which seems to back up Beeching’s analysis of the situation as a “fallout”. At an occasion such as Pride Month, artists coming out as bi/pan/queer would be top celebratory material for celebrities and their PR teams to repost and post comments on (to ‘drive up engagement’ and to of course, genuinely express solidarity and joy). No comment from fellow queer/sapphic icons in the pop genre, not even from Hayley Kiyoko, with whom FLETCHER co-released the flirtatious single Cherry in 2021. Here, as often is the case, the silence speaks volumes, and that’s what you need to read into as a communications professional, among all the noise and polarised keyboard debates.

What seems to be the problem

What I question as a communications professional are the following:

- How was Capitol Records, one of the largest record labels in the world, unable to foresee what Beeching has dubbed a “A masterclass in how not to handle audience connection”?

- Is it possible that FLETCHER does not have the experienced professionals one might expect for an artist of this calibre in the queer music sphere? Do queer artists receive the support and context-based community support their fans need (and increasingly, demand)?

- (Somewhat a tangent): Is there a labour union that artists like FLETCHER can rely on, or their PR/Comms team can be part of, to receive a “do’s and don’t” on running campaigns around sensitive subjects like sexual identity? Is there a committee for queer representation in the music industry?

With my first two questions, I started by doing what any communications professional does: looking up FLETCHER’s online presence. I noticed a few things that seem to indicate that her accounts aren’t as crafted or updated as I’d expected.

Interestingly, her official website is very US-centric, her website being hosted by Incapsula Inc., an California-based company, and her shop directly through Universal Music Group. Only US based fans are able to purchase merch, whereas most global artists would choose a third-party handling and shipping service like Shopify, that would serve internationally. In a very quick and randomised search, I only found one other queer/sapphic artist whose website is hosted by the same US company: Chapelle Roan. It would be interesting to investigate what this company offers.

- Billie Eilish, Lady Gaga, and Renee Rapp: Shopify

- Halsey, Hannah Gadsby, and Hayley Kikoyo: Cloudflare

- Tegan and Sarah and Nikkie Tutorials: hosted by local US/Dutch companies

The Capitol Records landing page also does not contain a placeholder or banner announcing a pre-sale for the new album’s vinyl records, which shows a lack of coordination, as the products are available through FLETCHER’s own website.

![A screencap of Fletcher's landing page on Capitol Records, sorted from Newest to Oldest. Vinyls do feature The Antidote, Doing Better, and Eras of Us, but not Boy, or mention a pre-sale for Would You Still Love Me [...].](https://realkoreans.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/screenshot-2025-06-08-at-21.06.23.png?w=1024)

Scanning Instagram, Facebook, and X, I noticed that the new “campaign” was timed around June 3, and June 5 (the day Boy was launched), with no engagement from her accounts to fans’ reactions or comments. It seems like a reactive, laissez-faire campaign, more damage control before a compromising paparazzi photo or third-party statement is released. And once they’ve leapt over that hurdle, the team has momentarily dissolved, relegating to moderating the comment section only because at the very least, they said it first.

FLETCHER’s social media presence doesn’t seem very curated: her Facebook photos aren’t even organised by albums. Her X/Twitter feed often reposts her fan pages, and sometimes posts “i’m alive xx” updates with sporadic outfit shots. The Instagram account no longer shows any posts prior to June 3, when her new campaign was launched (this isn’t unusual: many artists hide older posts temporarily to drive focus onto the new content). Her TikTok videos seem to be very sporadic as well.

All in all, I wonder if FLETCHER has a dedicated social media team. It seems like it may be either a single person trying to manage all platforms at once (this would explain the sporadic posting), that her management hires contractors only during peak moments like tours or releases, or that she’s one of many artists the Comms team collectively manages.

Do queer artists have access to the professional market analysis and PR that they need?

I assume that a record label works just like any other company. In that case, it’s impossible for a decision such as a new single/album/campaign launch to just come from the artist, unless they’re signed to an indie or self-owned label. It’s simply too high risk. We may safely assume that most, if not all, we see, read, and hear on the Internet does not come from FLETCHER herself, but through a crafted script and a (somewhat) dedicated team in A&R, HR, Legal, Communications, etc, etc. Songs may be written by someone, but edited, approved, recorded, edited, and polished.

Someone making an announcement that would pivot them from an image they’ve crafted over a decade deserves a dedicated campaign. It’s not simply about ethics and celebrating their development as a person and artist but also about strategy and marketing. Reactive campaigns can be beautifully authentic and celebratory and vulnerable, and FLETCHER’s Boy campaign did not deliver that. For example, when Nikkie de Jager [NikkieTutorials] came out in January 2020 after someone threatened to expose her trans identity, her fans stood by her and rejoiced, effectively neutering the blackmailer. Queer coming-outs can be opportunities. When Billie Eilish, after years of speculation, came out, first with a Variety interview in 2023, and then with the song LUNCH in 2024, it highlighted the authenticity of her brand, that of a young, honest, and socially engaged artist.

So when language in songs like Boy are approved—Where a lesbian icon seems to say, in her well-established confessional style, that being in a heterosexual relationship is something she’s had to hide (she does not mention both men and women, as she did in her previous songs alluding to her bisexuality), that it deserves a big reveal, and hints that she’s ashamed of her past as a woman loving women, and this is launched during the one month that’s meant to celebrate queerness, it says something about the system surrounding her:

I’ve been hiding out in Northern California

Where nobody knows who I was before

I’m scared to think of what you’ll think of me

The single even goes on to anticipate backlash from her lesbian/sapphic/wlw fans (in a manner similar to how one may anticipate hate for coming out as queer), in what seems like a taunt and a shrug mixed into one:

And it wasn’t on your bingo card this year

[…] You can think that I’m a hypocrite, that’s cool

I’m just following my heart, is what it is

As if in 2025, we needed a reminder that same-sex relationships do not enjoy the social or legal status as heterosexual relationships on most of the world, and continue to be criminalised in 62 countries, including a dozen in which it is punishable by death. Heterosexuality isn’t punishable by law anywhere (duh).

Finding Fletcher: What’s Next?

I listened to FLETCHER on repeat when I came out of my first queer heartbreak. Songs like Girl of My Dreams (2021) especially resonated with me:

Number one was a boy, and he had the greenest eyes

Like a forest, but I knew that I was lost

Round two in the city, she was crazy, but she made it so pretty

Left me emptier than lonely in New York

And three, she was an angel, yeah she could’ve been the one

But forever only made a couple trips around the sun

Personally, I can identify with the core message in Boy: anticipating biphobia. I remember coming out as lesbian at 19, and later, at age 21, when I realised I also felt attracted to men. I lost contact with many gay and lesbian friends, who believed that I had not been honest with them. In reality, like many young queer people, I simply did not have the life experiences to be certain about oneself (I only started dating at 24).

Many bisexual women friends of mine need to constantly defend their identity because they are now in a committed relationship with a man. As recent as last week, a friend of mine hesitantly called herself a hasbian at a queer reading group, because women who used to date women but currently do not often need a disclaimer to justify their queerness. Several female friends of mine are bisexual but have only been in one committed relationship in their life (with a man), and while they are certain about their identity, but the world is not: they are often pressured to stop calling themselves queer.

Real bisexual visibility comes from being authentic, like FLETCHER has been in the past, with her raw, emotional honesty:

“As if I’m not what you’re waiting for

Like I’m not in your ending

Yeah, for now, we’ll both keep on pretending

—Pretending, In Search of the Antidote, 2024)“I don’t know you and it hurts

I told every one of my friends, you won’t get a lyric again

But Goddamn, here I fuckin’ am”

—Eras of Us, Girl of My Dreams, 2022)“But somethings you can’t undo

And one of them’s you”

—Undrunk, you ruined new york city for me, 2019

The only way forward for FLETCHER’s team is for them to step up and issue a formal apology for the tone deafness of this campaign, be honest about why it was so rushed, and depending on the content of the album set for release—delay its release and promise to dedicate time and resources to properly reconnect with her community. Let’s hope they can dig her out of the pit they’ve seem to thrown her into.

For my longtime followers who were expecting updates on the South Korean snap elections, I'm sorry to disappoint you, but Korea has become so mainstream that there are many thinkers who've analysed it succintly, especially on LinkedIn.

I was writing a longer piece on what I've been up to in the past decade as this blog has travelled with me from Seoul, to Lyon, to all around Europe, Arizona, and beyond, but sometimes the unexpected happens, like FLETCHER's new single.

I've got so much I haven't shared with you in the past years. Like the rise of feminist filmmakers in Korea, how North Korean human rights activism is flawed by design, and how you should protect yourself as an international nonprofit worker. It's coming soon, I promise!